Go-Urban (1973)

cancelled

Evolved into go-alrt

GO-Urban was an ambitious plan created by the Province of Ontario towards creating an urban transit network spanning across Metropolitan Toronto and two other large Ontario cities. It would utilise an experimental maglev system powered by linear induction motors and cost over $700 million 1973 dollars. The project was projected to fill the niche of intermediate capacity transit, a gap between low-capacity surface bus routes and high-capacity, high-cost underground subways.

The first major endeavour into large-scale transit planning by the province of Ontario was with the introduction of an urban transportation policy for Ontario in 1972.1 The suspension of further work of the Spadina Expressway in 1971 effectively shattered Metropolitan’s Toronto intricate plans for expressways crisscrossing the city, leaving a gap in the transportation needs for the region, with an incomplete expressway network and insufficient public transit options to replace it.2 In response, the provincial government’s urban transportation policy outlined several steps in combatting growing congestion in the region including subsidises for transit-related facilities, staggered working hour programs, expansion of computerized traffic control systems, and most notably, the introduction of a new six-line urban Intermediate Capacity Transit System (ICTS), later dubbed GO-Urban.3

Cancelled Expressways

The obstruction of the completion of the Spadina Expressway by the provincial government in the 1970s was the final straw for many of the other proposed expressways meant to span Metropolitan Toronto, creating issues with transportation plans after, which had planned for those expressways to play a crucial role in the transportation needs of the city and region.4

(Boris Spremo / Toronto Star) © Toronto Star, 1985. Reproduced under license.

The system, planned to fill the gap between low-capacity surface bus routes and costly but high capacity subway lines, was planned to run mostly above-ground along railway and hydro right-of-ways, as well as the median of streets, saving costs from tunnelling.5 It was envisioned to carry a maximum of 20,000 passengers per hour in the peak direction at an estimated cost of $13.4 million per mile (or ~$21.5 million per kilometre) compared to $25-40+ million per mile (~$40-$64 million per kilometre) for subways, which could carry a theoretical maximum of 40,000 passengers per hour in the peak direction.6

Study began for such a system began in 1969, and by 1972, eight companies were invited to submit proposals for the implementation of ICTS in Ontario.8 Three finalists were selected in late 1972, Ford Motors, Hawker-Siddeley, and Krauss-Maffei of West Germany, with the province finally choosing Krauss-Maffei’s magnetically suspended, linear induction motor propelled system.9 Their proposal called for small vehicles of only 20 feet long (6.09 metres) by 7.5 feet wide (2.29 metres) holding 20 passengers (12 passengers sitting and 8 standing) to operate on elevated guideways at planned frequencies of up to 20-seconds.10 Operations of the system were extremely flexible, with vehicles able to operate singly or coupled together in trainsets of up to six cars, all controlled by a central control centre. Stations were also to be automated, with platform screen doors and automated ticketing.11

finalists

The three finalists chosen all followed the people-mover concept of small vehicles running along guideways. From left, prototypes by Krauss-Maffei, Ford, and Hawker-Siddeley. The Krauss-Maffei system was the only one proposed to utilise magnetic attraction, with the other two companies utilising rubber tires.12

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 1973. Reproduced with permission.

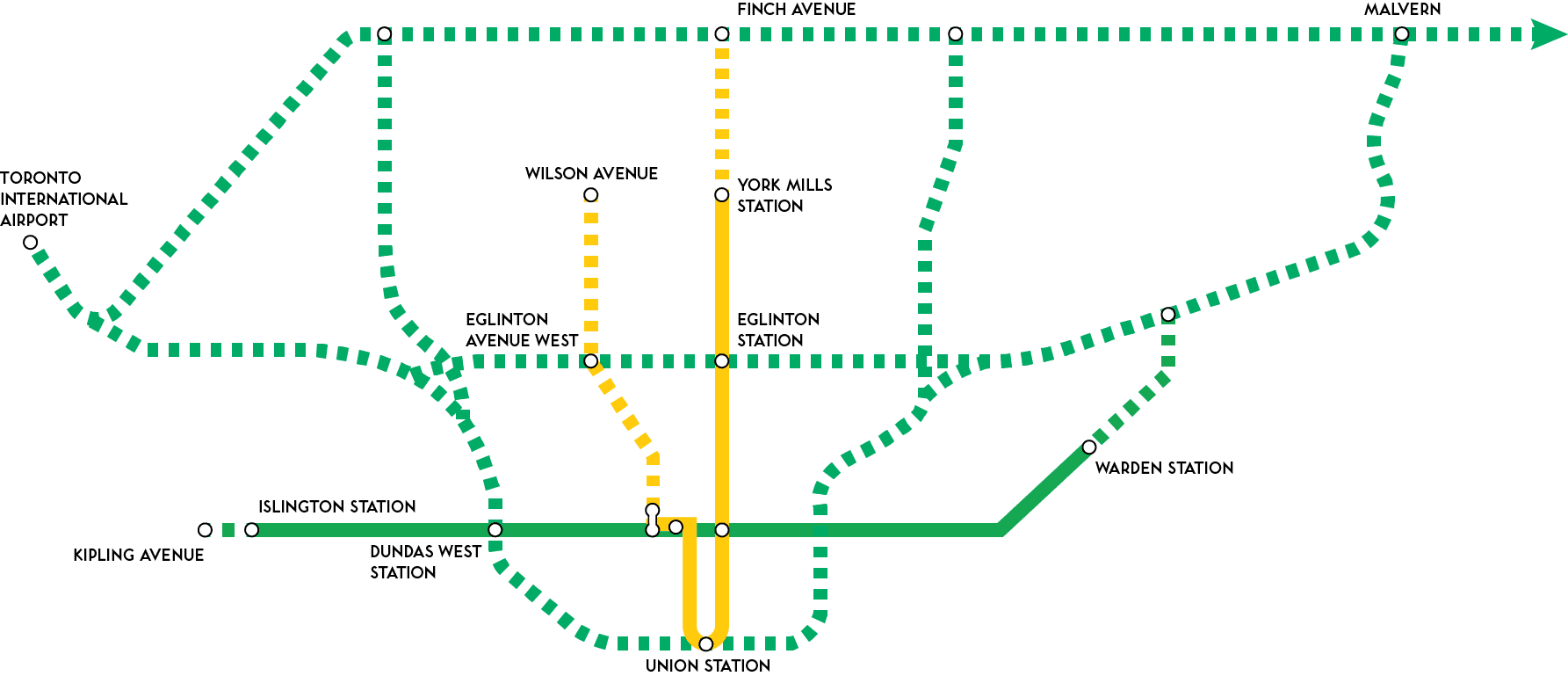

A 2.5-mile (4 kilometres) preliminary demonstration system with four stations began construction on the CNE grounds for testing of the system by the newly formed Ontario Transportation Development Corporation, which was tasked with developing future iterations of the system.13 Construction began on the demonstration line on August 23rd, 1973 and was projected to be completed in time for the 1975 CNE, with a possibility of permanently retaining the line after 1979 and extending it to Union Station.14 A larger, 56.1-mile (~90 kilometres) system costing an estimated $756 million and with five lines initially was proposed for Metropolitan Toronto, along with a two-line 11.4-mile (~18.3 kilometres) system in Ottawa costing $195 million and a three-line 17.3-mile (~27.8 kilometres) system in Hamilton, although the latter two systems never progressed past the drawing board.15

cne demonstration track

The CNE demonstration track would test the real-world applications of the technology for future implementation across Ontario. What began as a four station, 2.5-mile (4 kilometres) line costing $16 million quickly ballooned to over $25 million, with the station at Exhibition GO cut.16 The line was cancelled when the West German government pulled funding for Krauss-Maffei, which forced them to cancel their agreement with the Ontario government.17

Ontario Place Station

The CNE demonstration line would run elevated through the Exhibition grounds. Here, an artist’s rendition of the proposed Ontario Place station at the southern end of the grounds.18

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 1973. Reproduced with permission.

Within Metropolitan Toronto, the five routes proposed to be built first would both provide access to the downtown core and enhance east-west access through the city, with several of the routes roughly following the path of cancelled expressways. A sixth line was outlined but would be built at a future date.19

Elevated Maglev Transit

GO-Urban lines were envisioned to run through a diverse variety of urban landscapes. Several key lines were planned to run along existing railway and hydro right-of-ways on elevated guideways, while the crosstown route along Eglinton would have run underground in some sections. Other lines would have run alongside the street, elevated in the median or along the side. Here, images from a Government of Ontario brochure show renderings of how the GO-Urban system would have fit into Toronto’s urban fabric.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 1973. Reproduced with permission.

Beyond implementation of the system in Ontario, the provincial government received the exclusive rights and licenses for the sale and implementation of similar systems in South and Central America and the European Union, as well as a ten percent royalty for systems sold in the United States.29 Several urban centres in foreign markets were identified as potential markets for the system including Buenos Aires, Caracas, Melbourne, Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paulo, and Sydney.30

From the beginning of the announcement for the system, transportation planners were pessimistic of the plan, with some predicting that half of the network was infeasible and would not be built.31 Others were critical of the proposed routing of the line through Flemingdon Park, with planners adamant that an ICTS system would have insufficient capacity for the projected ridership, and that the proposed Queen TTC subway line, which would roughly follow the same route, would be needed instead.32 Opposition from Metropolitan Toronto and the TTC was also an issue, with TTC planners working on their own ICTS system utilising light rail vehicles, which the province criticised as being noisy and unsuitable for residential areas despite TTC reports saying otherwise.33 And while Metropolitan Toronto planners continued to plan for an extension of the Gardiner Expressway through Scarborough, the province was adamant that the new system would make the expressway unnecessary.34

Proposed Hamilton and Ottawa GO-Urban Systems

Besides Toronto, both potential lines in Hamilton and Ottawa were identified. Similar to the proposed routings for GO-Urban in Toronto, they were to follow streets, railway right-of-ways, and hydro corridors. In Ottawa, there would be a brief tunnel for the system under Sparks Street.35

The public was even less supportive of GO-Urban, with Scarborough residents calling the vehicles “flying coffins” in initial public consultations.36 Fears of the aesthetic impact of the system were confirmed when internal government reports revealed that GO-Urban stations would be double to triple the length of a subway station, either above ground or elevated, and with a width as wide as an arterial road.37 Meanwhile, Streetcars for Toronto, a transit advocate group originally formed to promote the retention of streetcars in Toronto highlighted the potential operational, cost, safety, and security issues with the proposed system, arguing that proven conventional light rail technology using streetcars would provide the capacity necessary for an ICTS system without such issues.38

Such issues with the system began soon during the testing stage. Beginning with delays to the demonstration line on the CNE, costs of the line soon rose dramatically from a budgeted $17 million to $25 million.39 Even after cutting “frills” and even one of the four stations from the line, construction was delayed past the 1975 opening date.40 In West Germany, where development of the technology was taking place, work was delayed as issues towards creating a working prototype continued.41 A scheduled trip by a provincial delegation was postponed from June 1974 to September 1974.42 Soon after the September visit, the completed prototype was damaged while testing as bugs continued to plague the system.43 Then, on November 7th, 1974, it was revealed that the system was incapable of reliably handling curves, cancelling another visit by provincial and municipal officials and dignitaries from Los Angeles, drawing ridicule from opposition parties in the provincial legislature.44

Krauss-Maffei Prototype

Pictured is the ill-fated prototype system under development by Krauss-Maffei in West Germany. After a series of delays, embarrassing bugs, and eventually a cut in funding, the GO-Urban plan was paused while development of the technology continued in Ontario. Although the maglev technology was unused, the linear induction motor technology was refined and serves as the backbone of several transit systems today.

The final straw came a week later on November 14th, when funding for the development of Krauss-Maffei’s ICTS technology was halted by the West German government.46 Krauss-Maffei was forced to withdraw from the GO-Urban project, and with the technology incomplete, GO-Urban was paused.47 Under the conditions of withdrawal, the Ontario government was allowed to retain exclusive rights to patents and the technology, as well as use of a test track of the system operational in Munich, West Germany for just under two years.48 The demonstration system under construction was cancelled, with a portion of the $25 million spent on the project to be refunded by Krauss-Maffei, while the rest of the lines planned under GO-Urban were put on hold pending further development of the technology by the province.49

Although provincial officials maintained that GO-Urban was not cancelled, the lines proposed as part of the project quickly faded into obscurity. One proposed line, the Malvern route, had a segment between the proposed Bloor-Danforth subway extension and Scarborough City Centre replaced with plans for a light rail transit line using streetcars, similar to what was originally proposed by Metropolitan Toronto and the TTC.50 The line would utilise new light rail vehicles developed by the same government agency tasked with GO-Urban, the Ontario Transportation Development Corporation, and would follow a similar route as what GO-Urban was planned to utilise.51 Eventually, plans for that line would change as well, with the province pressuring Metropolitan Toronto and the TTC to replace the light rail vehicles planned to be utilised on the line with GO-Urban’s successor – Urban Transportation Development Corporation’s (previously known as the Ontario Transportation Development Corporation) ICTS.52

Coupled Light Rail Vehicle

Light rail vehicles developed by the same Crown corporation tasked with research, development, and promotion of GO-Urban in Ontario were planned to be utilised for routes previously set for GO-Urban technology after its cancellation.53 The vehicles, later dubbed the CLRV (Canadian Light Rail Vehicle), were planned to be run in coupled pairs, as pictured, in their own dedicated right-of-ways, although the eventual shift in plans to utilise ICTS technology saw such plans dissipate.54 The same vehicles were the workhorse for Toronto’s streetcar fleet for over 40 years before their retirement in late 2019.

(David Cooper / Toronto Star) © Toronto Star, 1979. Reproduced under license.

Despite Ontario’s ambitions for ICTS across the province suffering a serious blow-back with the demise of GO-Urban, development for a system of similar purpose continued. Although magnetic levitation was shelved, the linear induction motor technology used to propel GO-Urban vehicles saw further development – this time with steel wheels to support it.55 Instead of small vehicles with a capacity of 20 passengers, the successor ICTS vehicle would hold 75 to 100 passengers and would run in trainsets of three to four vehicles.56 Dubious plans for 20 second frequencies for GO-Urban trains were replaced with possible frequencies to as low as 60 seconds a train.57 The new system was initially called Advanced Light Guideway Transit – ALGT, and was developed in partnership with a variety of companies including SPAR Aerospace, which constructed a test track for the successor project and Standard Electric Lorenz, a West German firm which was tasked with developing the automated train control system planned to be utilised.58

The successor system to GO-Urban was eventually completed and marketed as Urban Transportation Development Corporation’s ICTS and was meant to serve the same principle goals of filling a gap in the need for capacity between surface transit options such as buses and costly underground subways.59 Initially implemented in Toronto (in a section of the originally proposed GO-Urban route serving Scarborough), Vancouver (where it forms the backbone of their rapid transit system), and Detroit, updated versions of the technology continue to be used and implemented in cities across the world after the sale of Urban Transportation Development Corporation by the provincial government to Lavalin (and eventually to Bombardier).60

Scarborough Rapid Transit

GO-Urban’s legacy in Toronto today remains in the Scarborough Rapid Transit Line, which utilises both technologies developed from Krauss-Maffei’s initial work on linear induction motors as well as the route planned for GO-Urban through Scarborough.61

(Alan Dunlop / Toronto Star) © Toronto Star, 1985. Reproduced under license.

Ultimately, GO-Urban represented forward, if not slightly misguided thinking towards the future of urban transit. Fulfilling the need for an enticing alternative to the automobile through a high-frequency network of rapid transit, the plan was ultimately plagued by issues with the experimental technology utilised – with critics of the plan pointing out existing technologies such as light rail transit as proven alternatives. Although the province’s persistence in the further development of the technology never resulted in the ambitious network of ICTS lines as originally proposed in GO-Urban, the eventual product for such a system first envisioned by GO-Urban has played a significant role in fulfilling the transit needs of other cities worldwide.

Footnotes

- Canada. Ontario. Ministry of Transportation and Communications. Urban Transportation Policy for Ontario – A Statement by the Honourable William G. Davis Premier of Ontario. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 1972.

- Canada. Ontario. Ministry of Transportation and Communications. Urban Transportation Policy for Ontario – A Statement by the Honourable William G. Davis Premier of Ontario.

- Ibid.

- Boris Spremo. Expressway fears: The Allen Rd.; above; formerly known as the Spadina Expressway;; was stopped at Eglinton Ave. in the mid-‘70s after public outcry. Some Metro Politicians say transfortation will be the crucial issue over the next three years because of the rail lands development, 1985, black and white digital, Toronto Star photo archive, Toronto, accessed February 23, 2020, https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDMDC-TSPA_0115155F&R=DC-TSPA_0115155F&searchPageType=vrl

- Canada. Ontario. Ministry of Transportation and Communications. Urban Transportation Policy for Ontario – A Statement by the Honourable William G. Davis Premier of Ontario.

- Ibid.

- Canada. Ontario. Ministry of Transportation and Communications. GO-Urban – A Government of Ontario Project. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 1973.

- Canada. Ontario. Ministry of Transportation and Communications. GO-Urban – A Government of Ontario Project.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Canada. Ontario. Ministry of Transportation and Communications. Urban Transportation Policy for Ontario – A Statement by the Honourable William G. Davis Premier of Ontario.

- Canada. Ontario. Ministry of Transportation and Communications. GO-Urban – A Government of Ontario Project.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Robert, Williamson. “Davis Says Multi-Region Board to Run GO, Buses near Metro.” The Globe and Mail. August 24, 1973, sec. 5.

- Thomas, Coleman. “Germans Back out: Ontario Cancels Plan for Magnetic Trains.” The Globe and Mail. November 14, 1974, page 1.

- Canada. Ontario. Ministry of Transportation and Communications. GO-Urban – A Government of Ontario Project.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Pat, McNenly. “Airport Plan to Create a City of 150,000.” Toronto Star, March 3, 1973, sec. A1.

- Canada. Ontario. Ministry of Transportation and Communications. GO-Urban – A Government of Ontario Project.

- Canada. Ontario. Ministry of Transportation and Communications. GO-Urban – A Government of Ontario Project.

- Ibid.

- Thomas, Coleman. “Half of GO-Urban Plan Won't Be Built Experts Predict.” The Globe and Mail. October 11, 1973, page 47.

- Coleman. “Half of GO-Urban Plan Won't Be Built Experts Predict.” page 47.

- “TTC: 2 Rails Better for GO-Urban.” Toronto Star, November 27, 1973, sec. A4.

- Thomas, Coleman. “GRO 'Declares War' on Godfrey over Expressway.” The Globe and Mail. September 11, 1973, page 5.

- Canada. Ontario. Ministry of Transportation and Communications. GO-Urban – A Government of Ontario Project.

- Thomas, Coleman. “Elevated Train System Called 'Flying Coffin' by Skeptical Audience Members in Scarboro.” The Globe and Mail. September 12, 1973, page 1.

- “GO-Urban Stations Will Be Huge, Unsightly in Suburbs, Report Says.” The Globe and Mail. April 22, 1974, page 29.

- Thomas, Coleman. “Group Accuses Queen's Park of Naivete, Extravagance: GO-Urban Stems from Misjudgment of Metro Transit Needs, Street Car Boosters Say.” The Globe and Mail. November 12, 1973, page 5.

- “Delays, Cost Increases Plague GO-Urban Plan.” The Globe and Mail. May 7, 1974, page 5.

- “GO-Urban's Magnet Malfunction Makes Tories Target of Ridicule.” The Globe and Mail. November 8, 1973, page 3; Peter, Mosher. “Trains Won't Be Ready for the CNE: 'Elegance' of GO-Urban Track to Be Sacrificed for $2 Million Saving.” The Globe and Mail. May 22, 1974, page 31.

- “Work behind on GO-Urban, Firm Admits.” The Globe and Mail. May 4, 1974, page 4.

- “Work behind on GO-Urban, Firm Admits.” page 4.

- Thomas, Coleman. “Breakdown at Munich Test Site: Bugs Halt GO-Urban Train, Ontario Visit Off.” The Globe and Mail. October 29, 1974, page 4.

- “GO-Urban's Magnet Malfunction Makes Tories Target of Ridicule.” page 3; Thomas, Coleman. “'Would Be like Fire Blowout': GO-Urban Magnetic Train Having Trouble on Curves.” The Globe and Mail. November 7, 1973, page 1.

- Canada. Ontario. Ministry of Transportation and Communications. GO-Urban – A Government of Ontario Project.

- Coleman. “Germans Back out: Ontario Cancels Plan for Magnetic Trains.” page 1.

- Coleman. “Germans Back out: Ontario Cancels Plan for Magnetic Trains.” page 1.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Thomas, Coleman. “Ontario Revives Old Transit Plan in a Bid to Refurbish Its Image.” The Globe and Mail. January 10, 1975, page 5.

- Coleman. “Ontario Revives Old Transit Plan.” page 5.

- “Costs of Transit System Have Risen $47 Million.” The Globe and Mail. July 14, 1982, page 4.

- Coleman. “Ontario Revives Old Transit Plan.” page 5.

- “Costs of Transit System Have Risen $47 Million.” page 4; David Cooper. Spring is coming. Yes; it is; and that is about as soon as you will get a chance to board one of these new Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) Light Rail Vehicles (LRVs). They are four feet longer and seat three more passengers than the old cars. Until spring - maybe longer - they are being tested over every foot of TTC streetcar track in the Metro area, 1979, black and white digital, Toronto Star photo archive, Toronto, accessed February 16, 2020, https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDMDC-TSPA_0115612F&R=DC-TSPA_0115612F

- Michael, Moore. “$6 Million Spent on Successor to Magnetic Train as Ontario 'Picks up the Pieces of Krauss-Maffei'.” The Globe and Mail. May 14, 1976, page 1.

- Moore. “$6 Million Spent on Successor to Magnetic Train” page 1.

- Ibid.

- Thomas, Coleman. “GO-Urban Still Alive but End Product Could Change, Official Says.” The Globe and Mail. February 15, 1975, page 1.

- Paul, Palango. “Is Ontario on the Wrong Track?” The Globe and Mail. August 5, 1982, page 7.

- Russwurm, Lani and Nathan Baker. SkyTrain. English ed. ed. Toronto: Historica Canada, 2019.

- Alan Dunlop. Canada - Ontario - Toronto - Transit Commission - Rapid Transit - Scarborough LRT, 1985, colour digital, Toronto Star photo archive, Toronto, accessed February 16, 2020, https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDMDC-TSPA_0115590F&R=DC-TSPA_0115590F